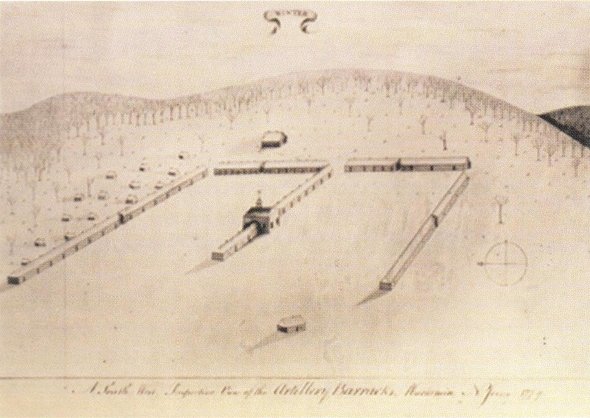

A South West Perspective View of the Artillery Barracks, Pluckemin, N. Jersey 1779

J. Lillie

The wind that swept across the Somerset Hills in the bitter winter of 1779 carried more than snow and smoke. It carried the sound of hammers striking timber, the commands of officers echoing across the ridges, and the heavy clatter of artillery wheels rolling over frozen earth. On the high ground above Pluckemin, the Continental Army was building something the young nation had never seen before. Lanterns swung in the darkness like small stars as the men worked through the long winter nights.

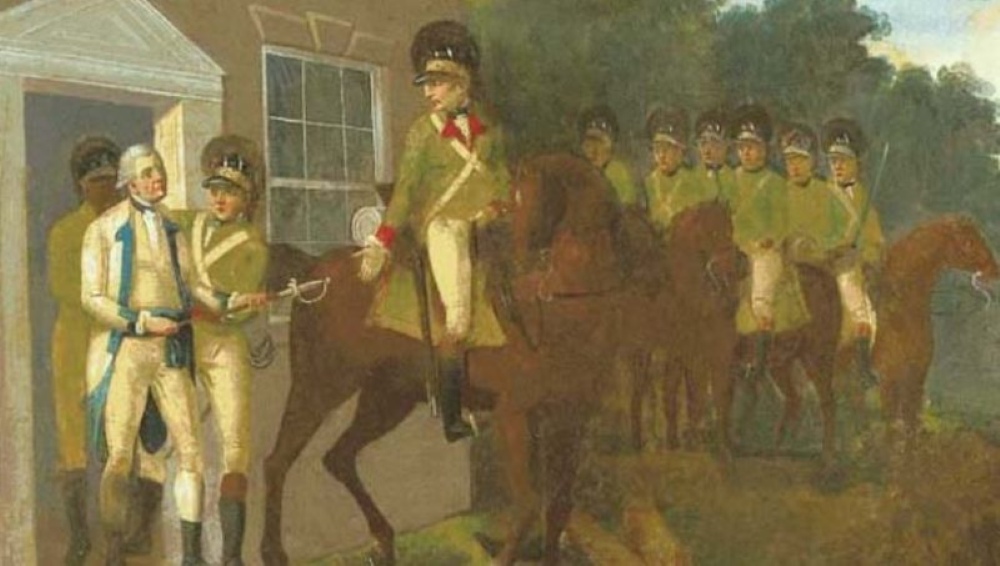

General Henry Knox stood at the center of it all, directing what would become the most advanced military installation of the Revolution. Barracks rose in perfect geometric lines. Workshops, storehouses, kitchens, and stables formed a village of soldiers. And at its heart, towering above the snow-covered landscape, stood the Artillery Academy, a grand structure of classrooms, laboratories, and lecture halls.

This was not a normal encampment. It was a center of learning, a place where officers studied gunnery, mathematics, philosophy, and engineering. It was the first military school in the new nation. Long before West Point was even imagined, the Army that Washington led into these hills was quietly preparing for a more organized future. And among the men who brought order to this winter world was a precise and thoughtful officer named John Lillie.

Captain John Lillie (Artist)

Captain John Lillie was born in Boston in 1737 and came of age in a world shaped by the busy wharves and fortified militia traditions of colonial Massachusetts. He was educated, patient, and exact in his work. These traits made him a natural fit for the field of artillery. Even before the Revolution, his mathematical skill and sense of discipline caught the attention of men like Henry Knox, who valued officers who could think as well as fight.

When the war began in 1775, Lillie joined the Boston artillery forces that ringed the city after Lexington and Concord. He served under Knox from the beginning, helping transform a small provincial artillery company into a true branch of the army. Through the campaigns in New York, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania, Lillie earned a reputation as one of the regiment’s dependable minds. He was not the loudest officer or the flashiest, but he was steady, trusted, and able to put complex ideas into clear form on paper.

By the winter of 1778 and 1779, when the artillery troops marched into Pluckemin, Lillie had gained experience not only as an officer but also as a recorder of the world around him. He had the rare ability to capture structure, proportion, and the sweep of a military landscape.

The Story of the Lillie Drawing

During the cold months at Pluckemin, Knox put his officers to work improving the discipline and science of the artillery. Classes were held daily. Equipment was repaired. Guns were tested on the surrounding hills. But Lillie saw something more. He saw that the cantonment itself was a creation worth remembering. Unlike any other winter encampment, it had an intentional plan. It was organized, geometric, almost elegant in its execution.

At some point in the first months of 1779, Lillie produced a remarkable image. Using ink, precision, and careful measurement, he drew a complete and detailed bird’s-eye view of the entire cantonment. He captured the long rows of barracks. He drew the officers’ quarters with their chimneys rising through the winter air. He mapped the roads that curved through the compound. He showed the large academy building that rose like a symbol of what the American artillery hoped to become. No other officer left anything like it. The drawing is the only contemporary visual record of the Pluckemin Artillery Cantonment. It is both map and memory, part engineering diagram and part portrait of a moment in the war when the Continental Army began to grow into a permanent institution.

Lillie could not have known that his work would survive the centuries. He simply recorded what he saw with the skill of a careful soldier who believed that accuracy mattered. Today, that drawing is one of the most important artifacts of the entire cantonment story. It preserves a world that vanished almost as soon as the snow melted in 1779.

Max Goes Looking for Knox Artillery Camp

More than a century after Knox and Lillie left the Pluckemin hillside, the first modern searcher arrived. His name was Henry Max Schrabisch, an early New Jersey archaeologist hired by Grant Schley in nineteen sixteen to locate the long-forgotten artillery cantonment.

Armed only with a shovel, a notebook, and local rumor, Max climbed the slope above Pluckemin three separate times over two seasons. What he found were long rows of low stone mounds along the base of the ridge. He opened trench after trench through them, uncovering fireplaces, ash, and scattered 18th-century debris. Max had located part of the camp, the line of barracks at the foot of the hill.

But Max was working blind. He never mapped the full encampment, never reached the higher ground where the great academy once stood, and most importantly, he had no access or knowledge of the Lillie drawing. That remarkable perspective would not appear in the historical record until twenty years later. Max proved the camp was real, but the complete plan of Knox’s artillery village would have to wait for another generation of researchers, Cliff Sekel and John Seidel, who would pick up the search with better tools and, this time, with Lilly’s work in hand.

In Comes Cliff Sekel

Clifford Sekel Jr., a New Jersey historian born in Bayonne, later lived in Somerville and Sunset Lake (nearby), close to the Pluckemin hillside he had studied for so many years. In the late 1960s, he began walking the fields, studying old deeds, and gathering every surviving document connected to Knox’s artillery. His graduate work produced a major study in 1972 titled The Continental Artillery in Winter Encampment at Pluckemin, New Jersey, December 1778 to June 1779. It was the first modern attempt to tell the full story of the site using archival research rather than memory or speculation. He later completed a doctorate at Kansas State University.

By the time Cliff began working with a young archaeologist named John Seidel in 1979, he already knew of a wartime drawing preserved in the Morristown National Historical Park files. When staff finally brought out the original sheet titled “A South West Perspective View of the Artillery Barracks Pluckemin, New Jersey 1779,” signed by John Lillie, both Sekel and Seidel immediately recognized what they were seeing. It was the only known visual record of the cantonment. Cliff provided the documentary foundation. Seidel carried the fieldwork forward, helping launch the Pluckemin Archaeological Project in 1980 and later completing his University of Pennsylvania doctorate on the archaeology of the American Revolution with Pluckemin as the central case. Together, they linked the paper world of Lillies’ drawing to the physical remains still buried in the hillside.

Then Came the Twist Many Don’t Know: Lillie Drawing Goes Missing

At some point between when the Lillie drawing was put into the archives, probably around the 1970s, it slipped out of its vault at Morristown National Historical Park. It was a fragile sheet no larger than a writing tablet, thin enough to slide between other papers and light enough to lift without anyone noticing. At a time when the National Park Service and the National Archives were still arguing over who should safeguard the nation’s earliest documents, the drawing remained in the park collection as an artifact rather than a formal government record. That made it vulnerable.

What happened next, I did not learn from an archive or a report. I learned it in broad daylight while standing around a kitchen island in Chester, sharing a bourbon with Matt Koppinger, who had lived the story himself. Koppinger told me that the drawing had been taken by a federal employee with access to the vault. When its disappearance was discovered and word reached Washington, the FBI became involved. The artifact was federal property and the only surviving image of Knox’s cantonment.

Matt explained how he became an unexpected part of the effort to get it back. Because he knew the people and the local community, he was asked to help calm the situation and keep communication open. He became an informal go-between, speaking carefully with the individual who held the drawing while investigators waited for the right moment to act. As pressure increased, the thief panicked and threatened to burn the drawing rather than surrender it. One reckless moment could have erased the entire visual memory of the Pluckemin cantonment.

Koppinger described the tension of those conversations, the careful pacing, the need to choose every word with precision. His task was to keep the thief steady and talking long enough for the FBI to intervene, and to prevent the only wartime image of the artillery academy from being destroyed forever. Standing there in his bright kitchen, sunlight coming through the windows and that bourbon glass on the counter, he spoke with a seriousness that made the past feel very close.

After hearing his account, I went to Morristown National Historical Park a few months later and requested a meeting with the superintendent. In that meeting, the Park Superintendent neither confirmed nor denied the story. He listened, answered cautiously, and then told me that I would not be permitted to see the original document. His tone made it clear that whatever had happened was known and remembered, and that the Park Service had no intention of revisiting it.

In the end, the FBI recovered the drawing intact and returned it to Morristown, where it remains today. It is a chapter almost no one knows, but without federal agents and Matt Koppinger’s efforts, the Lillie drawing could have been lost forever, and that would have been a really bad outcome.

John Seidel Now Had the Lillie Drawing

When John Seidel stepped into the Pluckemin story in 1979, he brought something entirely new to the search: modern archaeological method and early computer-based analysis. Working alongside Cliff Sekel, Seidel used controlled excavation grids, soil chemistry testing, artifact distribution mapping, and one of the first generations of digital data plotting to rebuild the cantonment layout step by step. Every hearth uncovered, every refuse pit, every line of stone or posthole was recorded, cataloged, and plotted with a precision the site had never seen before.

Seidel Finally Finds the Exact Location

The more data that emerged from the hillside, the clearer the pattern became. When Seidel overlaid the archaeological results onto the 18th-century perspective drawn by Captain John Lillie in 1779, the alignment was unmistakable. The barracks lines matched. The officers’ quarters matched. Even the slope of the ground and the position of the workshops came together exactly as Lillie had shown it. Seidel had proven that the drawing was both authentic and accurate, and that it captured the cantonment in a way no written description ever could.

Seidel mentions the Lillie document and the theft on pages 23-24 of his report (see above).

Through Seidel’s work, the Lillie drawing was no longer just a historical curiosity. It became the structural blueprint for understanding America’s first artillery academy. His research confirmed that Lillie’s careful strokes on paper reflected the site’s true geometry, and that the winters of 1778 and 1779 had produced a military complex far more advanced than anyone had imagined.