December 13, 1776, stands as the most electrifying day in Basking Ridge’s history, when the sleepy colonial crossroads suddenly became the center of the Revolution. At dawn, the infamous capture of General Charles Lee sent shockwaves through Washington’s struggling army and the entire young nation. British dragoons thundered down the roads, militia scrambled in confusion, and a single moment on a frosty Basking Ridge morning changed the trajectory of the war. It was the day our town became the stage for one of the Revolution’s boldest and most consequential twists.

Because Basking Ridge is home to the Mr. Local History nonprofit, this moment is more than a passing footnote; it is the heartbeat of a story we are uniquely positioned to tell. What happened here on that cold December morning is now unfolding in a series of posts that explore the people involved, the landscape that shaped their decisions, and the far-reaching impact of this single event on American history. By situating the narrative in the place where it occurred, we can bring readers closer to the tension, the personalities, and the significance of a turning point that helped alter the fate of the Revolution.

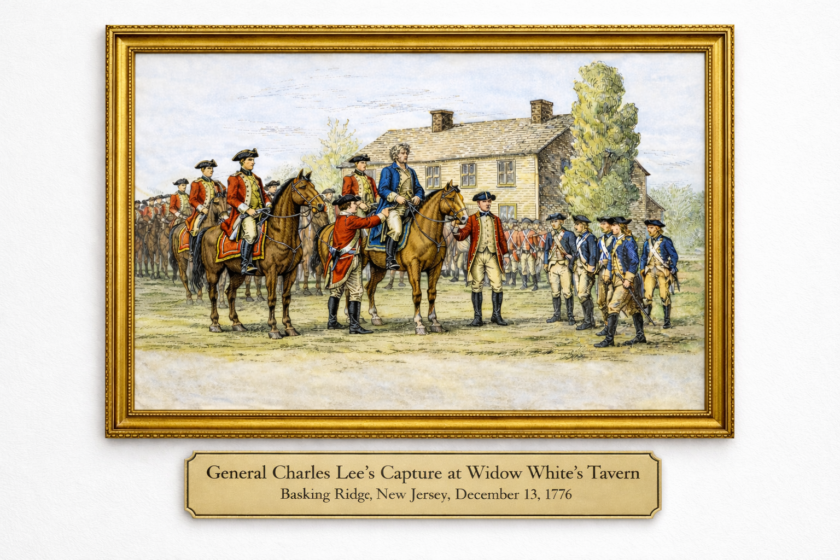

Oscar M Voorhees’ 1933 lecture retells the dramatic capture of General Charles Lee at Widow White’s Tavern in Basking Ridge on December 13, 1776. Voorhees places strong emphasis on the local geography, ownership of the tavern property, and the context of the surrounding farms and early roads. He explains that Lee, second-in-command of the Continental Army, operated independently of Washington, moving slowly across New Jersey, often ignoring direct orders, and staying in civilian homes rather than with his troops.

As Lee lingered at the tavern with only a small guard, British dragoons under Lt Col William Harcourt executed a rapid, surprise cavalry raid from the direction of Pennington. They overwhelmed Lee’s guards and seized him in his bedroom. The lecture highlights differing historical accounts (letters, memoirs, fiction), and gives vivid descriptions of the tavern setting, local characters, and Lee’s temperament. Voorhees emphasizes that the geography of the Somerset Hills shaped both the event and the military situation in late 1776, ultimately leading to the turning point at Trenton after Washington regrouped.

The Local History Collection holds the original paper at the Bernards Township Library

The Letter General Lee Was Writing to General Horatio Gates While at Widow White’s

On the freezing morning of December 13, 1776, General Charles Lee sat inside Widow Whites Tavern at Basking Ridge finishing a private letter to General Horatio Gates. The note crackled with frustration. Lee wrote that the fall of Fort Washington had “unhinged the goodly fabric” of the American cause and complained that a “certain great man,” his thinly veiled swipe at General George Washington, was “most damnably deficient.” He described his situation in New Jersey as desperate: no cavalry, no shoes, no money, surrounded by Loyalists, and facing what he believed could be the final collapse of the Revolution.

The letter revealed a man torn between ambition and duty. Instead of hurrying to join Washington on the Delaware as he had been ordered, Lee lingered behind, convinced he could manage the crisis better on his own terms. He admitted to Gates that every path before him involved danger, yet he delayed, sure he could still salvage the campaign. He closed the letter with a dire warning that unless something unexpected occurred, “we are lost.”

Lee had barely sealed the letter when British dragoons galloped into the yard. Within minutes, he was captured, still wearing his dressing gown. The dramatic contrast between his bold words and the sudden arrival of his captors heightens the moment’s lasting impact. The very independence Lee believed would save the army instead led directly to his downfall on a quiet December morning in Basking Ridge.

Letter from General Charles Lee to General Horatio Gates

Dated: Basking Ridge, December 13, 1776

“The ingenious manoeuvre of Fort Washington has unhinged the goodly fabrick we had been building, there never was so damnd a stroke, entre nous a certain great Man is most damnably deficient. He has thrown me into a situation where I have my choice of difficulties. If I stay in this Province I risk myself and Army and if I do not stay the Province is lost for ever. I have neither guides Cavalry Medicines Money Shoes or Stockings. I must act with the greatest circumspection. Tories are in my front rear and on my flanks, the Mass of the People is strangely contaminated. In short unless something which I do not expect turns up We are lost. Our Counsels have been weak to the last degree. As to what relates to yourself if you think you can be in time to aid the General I would have you by all means go. You will at least save your army. It is said that the Whigs are determined to set fire to Philadelphia. If They strike this decisive stroke the day will be our own, but unless it is done all chance of Liberty in any part of the Globe is for ever vanished.”

Why Lee Was in Basking Ridge – The Breakfast Meeting He Missed

John Morton’s daughter, Eliza, writes about her early days in Basking Ridge and the December 13, 1776, capture of General Lee at Widow White’s Tavern, just down the street near Colonial Drive. The Mortons lived on North Maple Avenue behind the Basking Ridge Presbyterian Church at the time. John Morton was known to Washington and others as the “Rebel Banker” and as one of the wealthiest financiers supporting the Continental Army’s war effort.

One of my first memories of the war was my father, who was always attentive to every officer of the army, calling on General Lee and inviting him to breakfast the next day. He accepted, but as he did not appear at the appointed time, Mr. Morton became impatient and walked up the hill to meet his expected guest. On his way, he encountered the country people running in great consternation, exclaiming, ‘The British have come to take General Lee!’ My father hurried on and saw Lee, without hat or cloak, forcibly mounted and carried off by a troop of horse; and as he had but few attendants, but little resistance was attempted. One of his men, who offered to defend him, was cut down and wounded by the sabers of the horsemen. He was brought to our house, where he was taken care of until he was carried on a litter to a surgeon in Mendham.“

Think About It for a Moment……

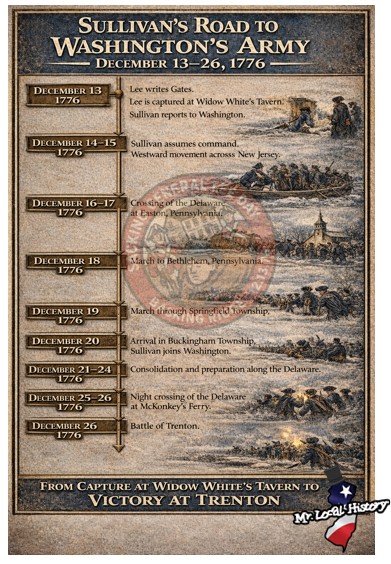

When Charles Lee was captured on December 13 1776 in Basking Ridge, his main body of troops was not captured with him. Most of his command was camped and quartered around Vealtown (Bernardsville) and nearby northern New Jersey towns. With Lee gone, Major General John Sullivan took over and immediately focused on pulling the scattered regiments together and getting them moving to Washington as fast as possible.

Sullivan drove the column west to the Delaware River and crossed into Pennsylvania at Easton on December 16 and December 17. From there they marched to Bethlehem on December 18, passed through Springfield Township in northern Bucks County on December 19, and arrived late on December 20 in Buckingham Township a few miles west of Coryell’s Ferry, essentially joining Washington’s camp in the Delaware River corridor.

Lee had commanded roughly 2500 men on paper earlier in that period, but by the time Sullivan delivered the division to Washington on December 20 the number had shrunk to about 2000, with many men exhausted, sick, or otherwise unfit after the hard march and expiring enlistments. Those troops helped rebuild Washington’s army in the days immediately before the Trenton operation.

Finally, on the night of December 25, 1776, the war that Lee believed was collapsing exploded back to life. While Lee sat in British custody, Washington crossed the Delaware with about 2400 men in the main striking force, and the former Lee division under Sullivan made up a large share of the troops Washington now had available, alongside other arriving units and men detailed away to guard ferries and supplies. That surprise attack on Trenton the next morning became the first major American victory of the Revolution and revived a cause that many believed was finished. The triumph at Trenton proved that the American army was still alive, and it marked the beginning of the remarkable turnaround that would define the winter campaign.

In the end, if General Lee wasn’t captured in Basking Ridge, Lee’s 2,400+ soldiers may have never made it to cross the Delware and take Trenton, and the war most likely would have ended the American dream for independence.

About Oscar Vorhees

Reverend Oscar M. Voorhees was a minister at the Basking Ridge Presbyterian Church (1913 until roughly 1944), a local historian, and a genealogist who spent much of his life documenting church and family history in New Jersey. He was born in 1864 and died in 1947. He served in the orbit of the Basking Ridge Presbyterian Church as a writer and editor of historical materials (for example, he prepared addenda to Rankin’s historical discourses on the church), and he also founded the Van Voorhees Association in 1932 to preserve his Dutch family’s history. Later in life, he became the official historian of Phi Beta Kappa and spent about 10 years producing The History of Phi Beta Kappa, published in 1945.

Rev. Dr. Oscar M. Voorhees descended from the Whitaker family of Mine Brook, Somerset County, New Jersey, the same extended Whitaker family associated with Widow White (Mary Whitaker Brown White). So it’s great to see Oscar weigh in on the historic event at White’s Tavern.

He wrote “General Charles Lee and his capture at Widow White’s Tavern, Basking Ridge, NJ” as a paper read before the Basking Ridge Historical Society on February 18, 1933, and that is how it is cataloged today in local history references and at Bernards Township Library. The “why” is clearly in his lane: he was trying to determine the regional setting of a nationally significant Revolutionary War episode, using church records, land ownership, and road patterns around Basking Ridge to show precisely where and how Lee was captured. In other words, he was doing in 1933 what you are doing now with Mr Local History: taking a famous story and rooting it tightly in the real geography and families of the Somerset Hills so the community would not lose that connection.

Timeline After Lee’s Capture by the British

The capture of General Charles Lee at Widow Whites Tavern in Basking Ridge on December 13 1776 very likely changed the timing of the Continental Army at a critical moment. In the weeks before his capture, Lee had repeatedly delayed marching his troops despite direct and increasingly urgent orders from George Washington to move toward the Delaware.

Washington was already concerned that Lees force might arrive too late to affect events, and time was running out as enlistments expired and morale collapsed. Once Lee was taken, command immediately passed to General John Sullivan, who acted decisively. Within days, the scattered regiments were concentrated, marched west across New Jersey, crossed the Delaware at Easton on December 16 and 17, and reached Bucks County by December 20. Those troops were in place just days before Washington issued his final orders for the December 25 crossing. While it cannot be proven that Lee would have missed the deadline entirely, the documented pattern of delay makes it reasonable to conclude that his capture increased the likelihood that these men might not be present for the Trenton campaign. In that narrow window between collapse and counterattack, removing a hesitant commander and replacing him with one who moved immediately may have made the difference between action and inaction, departure of soldiers to re-up in the new year.

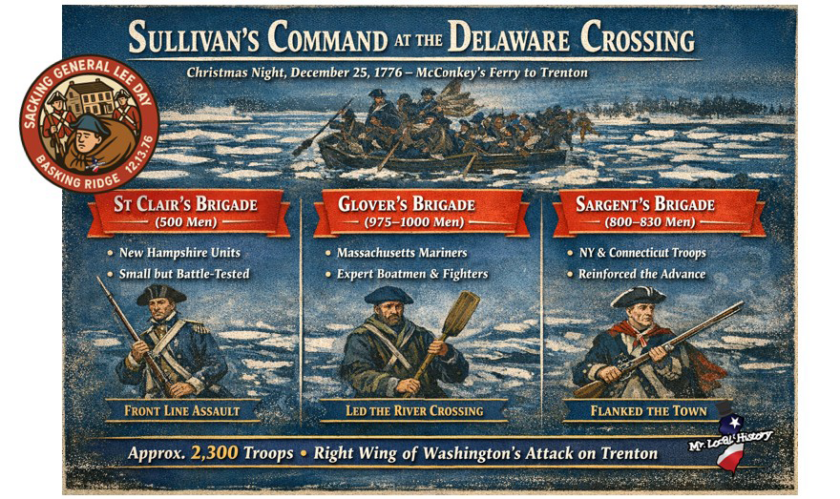

By Christmas night, Sullivan’s column composed of St Clair’s Brigade (500), Glover’s Brigade (975 to 1000), and Sargent’s Brigade (800 to 830) numbered roughly 2300 effective officers and men. These were largely the same troops who had been detached with Lee near Vealtown, survived his capture, marched west across New Jersey and Pennsylvania, and then formed the right wing of Washington’s army as it crossed the Delaware at McConkey’s Ferry and struck Trenton.

In eighteenth century military terms, the right wing was not a ceremonial label. It meant the main body of infantry assigned to cross first, move along the river road, and enter the enemy position from the most direct approach. Sullivan’s right wing bore the brunt of the night march, the river crossing, and the opening attack at Trenton, while other columns supported or protected the operation.

In Their Own Words

After the capture of General Charles Lee at White’s Tavern in Basking Ridge, New Jersey, the 2nd in command, Major General John Sullivan, took control of 2000-2500 Continental Army soldiers and immediately marched west across New Jersey, crossed the Delaware River, then south to Buckingham, PA, in just 7 days to meet up with General Washington. It’s important to note that only 2,400 troops crossed the Delaware River that cold night on December 25, 1776.

Sullivan reported that about 70 British light horse surrounded the house at White’s Tavern near Basking Ridge on the morning of December 13, 1776 and that General Charles Lee was taken prisoner. Trumbull added that besides Lee, the only others taken were 1 British light horseman and 1 French volunteer, identified in the editorial notes as Sieur Gaiault de Boisbertrand. Both accounts note that some of Lee’s guard escaped and that some were wounded, with no deaths stated in those letters.

Inside the tavern, seconds mattered. Captain Jean Louis de Virieux, a French volunteer officer serving with Lee, is described as defending the front entrance while the British seized Lee in the confusion. The British then rode off without searching the tavern, and that single oversight opened a narrow escape route for Lee’s aides de camp, William Bradford and James Wilkinson. ¹ Wilkinson’s escape mattered immediately because Sullivan was able to write Washington the same day with a coherent report confirming that Lee was gone but the troops were not. Command did not collapse into panic. Instead the force stabilized under Sullivan and continued its movement toward the Delaware, keeping alive the chain of events that would lead to the Christmas night crossing and the Battle of Trenton victory.

¹ Founders Online, Washington Papers and related editorial notes and correspondence.

Sullivan told Washington that on the morning of December 13, 1776, “70 of the Light Horse surrounded the House” and that General Charles Lee “was made a prisoner.” 1 Trumbull, writing the same day, pinned it to place and time, reporting Lee was taken “at White’s Tavern, near Basking ridge, about 10 oClock this Morning,” and adding that “Majr Bradford is Just come in,” with the situation then understood as Lee taken and others mostly slipping away, aside from “one of the French gentlemen,” identified in the editors note as Sieur Gaiault de Boisbertrand. 2 Then comes the lived moment from Wilkinson, who later wrote that he saw “a party of British dragoons” charge in, and that once Harcourt rode off with Lee, he “mounted the first horse I could find, and rode full speed to General Sullivan,” linking the doorway chaos directly to Sullivan’s rapid assumption of command. 3

1 Major General John Sullivan to George Washington, December 13, 1776, Founders Online. Founders Online

2 Joseph Trumbull to George Washington, December 13, 1776, Founders Online. Founders Online

3 James Wilkinson, Memoirs of My Own Times, volume 1, full text via Internet Archive. Internet Archive+1

General Lee Basking Ridge Capture Series

Widow White’s Tavern Series – A Basking Ridge American History Moment

Views: 208 December 13, 1776, stands as the most electrifying day in Basking Ridge’s history, when the sleepy colonial crossroads suddenly became the center of the Revolution. At dawn, the infamous capture of General Charles Lee sent shockwaves through Washington’s…

December 13, 1776 – Basking Ridge , New Jersey Altered American History

Views: 8,510 The world might have had a different look if it weren’t for this day’s event.December 13, 1776 in Basking Ridge, New Jersey. Basking Ridge, New Jersey’s most famous incident, occurred on December 13, 1776, at about noon. General…

New Jersey Rev War Series Mr. Local History Project

Views: 10,155 New Jersey is known as the “Cockpit of the American Revolution” for a reason – because it was. More battles, more encampments, more strategies took place in New Jersey than in any other colony of the original thirteen.…

Widow White – Mary Jarvis Whitaker Brown White

Views: 970 This is a story about a widow, a General, and a War for Independence. For over a decade, I’ve been researching the story behind the 1776 capture of one of General Washington’s head generals, but I never really…

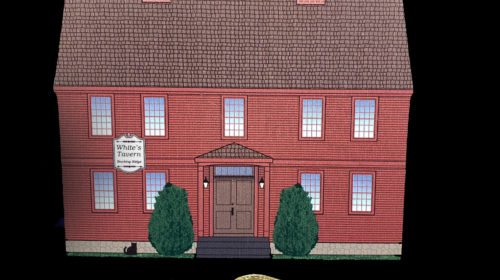

Widow White’s Tavern in Basking Ridge was More Than a Grog Stop

Views: 27,048 Basking Ridge, New Jersey’s Most Famous Incident Yes, this historic event made the series, so look for it. The episode covering that timeframe is Episode 3: “The Times That Try Men’s Souls (July 1776 – January 1777)” about…

Three Historic Moments That Changed Basking Ridge & America

Views: 11,726 On the internet, we’ve created the #3LOCALHISTORYEVENTCHALLENGE, where you share your town’s three most historic events. As the historian for Bernards Township, representing Bernards Towns#hip and its four hamlets is a great honor. We’re always looking for ways…

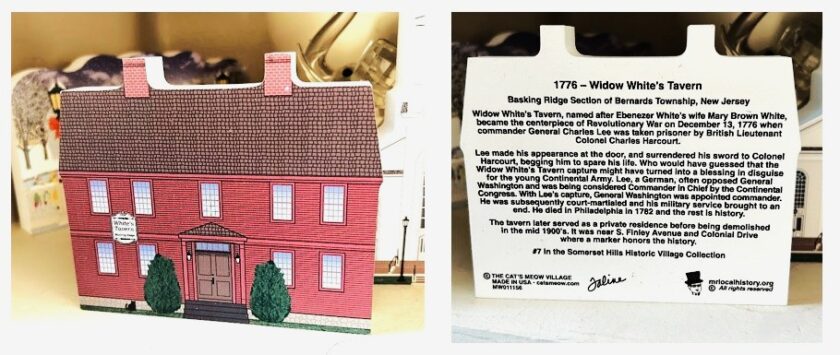

Widow White’s Tavern 7th Wooden Historic Village Keepsake

Views: 6,155 Be part of the Widow White’s Tavern limited edition run. Mr Local History is proud to announce the release of the 7th in the collectible series, the infamous 1776 Widow White’s Tavern in the village of Basking Ridge.…

John Morton – General Washington’s Rebel Banker Stashed in Basking Ridge

Views: 6,695 John Morton was a Colonel in the Continental Army. Still, he relinquished his commission in 1761 to become a highly successful merchant, specializing in the trade of flax from his native Ulster in Northern Ireland, thereby supporting the…

What Happened to Mary White and Widow White’s Tavern – Research Notepad

Views: 27,159 Below are the original research notes as I had spent years researching contradicting information on the Widow White’s Tavern in Basking Ridge, New Jersey. Often I like to post research in hopes that other researchers can see what’s…

Related Posts from Mr. Local History

Our Readers’ Top 10 MLH Posts this Week

| December 13 1776 | Lee writes Horatio Gates a letter that morning, and the text is preserved in the Gates Papers. This is evidence the letter reached Gates or his headquarters and was retained. |

| December 13 1776 | General Charles Lee is captured at Widow Whites Tavern in Basking Ridge New Jersey. The same morning, Major General John Sullivan writes George Washington reporting Lees capture and that the troops were not taken with him. |

| December 14 1776 | Regrouping phase in New Jersey under Sullivan after Lees capture. No single primary source in the references here gives a dated location line for this exact day, but Sullivans assumption of command is documented on December 13 and the Delaware crossing is documented beginning December 16. |

| December 15 1776 | Continued movement west across New Jersey toward the Delaware corridor, still between the documented command handoff and the documented Easton crossing. Same limitation as December 14 for a day stamped location line in the references listed. |

| December 16 1776 | Sullivans force, meaning the troops previously under Lee, begins crossing the Delaware River at Easton Pennsylvania. |

| December 17 1776 | Crossing at Easton continues. |

| December 18 1776 | The column marches to Bethlehem Pennsylvania. |

| December 19 1776 | The column passes through Springfield Township in northern Bucks County Pennsylvania. |

| December 20 1776 | The column arrives late in Buckingham Township Pennsylvania, a few miles west of Coryells Ferry, effectively joining Washingtons forces on the Pennsylvania side. |

| December 20 1776 | Sullivan arrives with the troops formerly under Lee and joins Washington in Pennsylvania, with the approach and arrival described in Washingtons letter written this day from the Newtown area. |

| December 21 1776 | Washington is consolidating forces on the Pennsylvania side and preparing an offensive move, while waiting on the arriving columns to fully close up after the Easton to Bucks County march. This date is best supported as a preparation day inside the window between the documented arrival by December 20 and the documented army strength statement on December 22. |

| December 22 1776 | Washington states Sullivan has just come up with the troops under Lee, about 2000 men, which anchors the approximate strength now present after Sullivans arrival and consolidation. |

| December 23 1776 | Final staging period along the Delaware in Pennsylvania as Washington continues planning and organizing for an attack across the river. This is the quiet build up between the documented force levels on December 22 and the issued crossing orders on December 25. |

| December 24 1776 | Operational preparations continue, with the army positioned to move on short notice once the crossing plan is activated. Primary documentation in this set resumes with the formal written orders issued December 25. |

| December 25 1776 | Washington issues General Orders directing the troops to assemble 1 mile back from McConkeys Ferry as darkness comes on, then march to the ferry and embark, establishing the official start of the Trenton operation crossing plan. |

| December 26 1776 | The Battle of Trenton is fought in the morning, after the night crossing. Washington reports the enterprise was executed the previous morning and describes it as a successful attack on the enemy detachment at Trenton. |